-

Distributing a given xG total into few, high quality shots will not maximise points return for some teams in certain match situations – in fact the opposite is true

-

Teams with a known and realised strength disadvantage will achieve increased points per game if their match xG total is distributed across a high number of lower quality shots compared to a low number of higher quality shots

In Part 1 we built a primitive xG match model in Excel to prove mathematically what Mark Taylor had demonstrated using brute force simulations. Namely that two teams with equal xG totals will have different expected points outcomes when the shooting chance quality is distributed differently. With a constant xG total, a low number of high quality chances outperformed a high number of low quality chances.

At the end we showed that this is indeed the case for varying xG totals with the low quantity-high quality chance team’s advantage differential increasing as the xG total increases.

We’ll now move away from the case where both teams have the same xG totals, and look at situations where a team could employ these two distinctive shooting strategies when weaker than their opponent. We will define being weaker as creating less match total xG than was conceded.

As always, its a good idea to define our environment first. Lets find two new teams: Weak City and Strong Athletic. Next we’ll define a new term: Strength Factor (SF). SF is simply the xG total for the Strong Athletic divided by the xG total for Weak City.

Let’s look first at how Weak City will get under varying shooting strategies against Strong Athletic. We will say that Strong Athletic’s xG total will be distributed over 15 shots every time, which can be said to be a plausible number for a strong team playing against a weak team.

We will also firstly set the SR = 2, so Strong Athletic’s xG Total will be twice that of Weak City. That’s all of our constants defined, now let’s look at the variables.

We’ll vary the match scenario over two variables: Weak City’s xG Total (remember Strong Athletics will always be 2x this value), and most importantly, the number of shots Weak City’s xG is distributed over in a game.

Like before, we’ll measure Weak City’s outcome using Points Per Game (PPG).

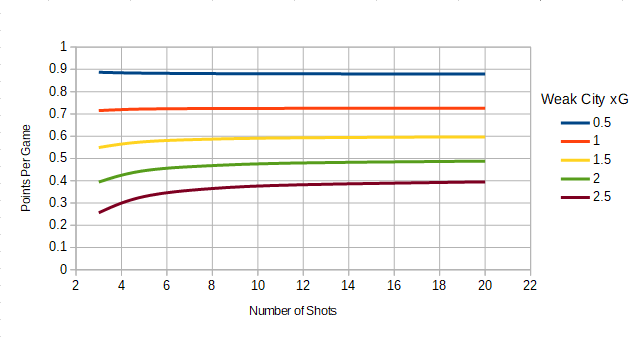

Weak City’s PPG performance is shown below, and it immediately throws up something that goes against the conclusion we came to previously.

Expected Points per Game vs Number of shots xG is distributed over - Opponent SR=2

But first lets comfort ourselves in reinforcing conventional wisdom by noting that when the xG total is lower, Weak City’s PPG increases. This is a well known result that makes perfect sense because in by keeping the number of chances in a match low, we’re maximising the influence that 0-0 has on the distribution of scores, which is beneficial for a weak team playing against a strong team.

We can also put some numbers to Weak City’s benefit of closing a game down as opposed to engaging in an end to end free for all. Remembering at all times Strong Athletic creates twice as much xG as Weak City, Weak City can be as much as 0.4-0.5 PPG better off keeping the game to a 0.5 vs 1 game (blue line) compared to a 2 vs 4 game (green line). The case for anti-football, if such a concept exists, could not be clearer.

Moving on to the more surprising outcome of our plot, it seems that when Weak City creates an xG of 1 vs Strong Athletic’s 2 and above, Weak City’s PPG outcome is better when it takes high quantity-low quality shots compared to taking low quantity-high quality shots.

This is at odds with what we previously saw when teams were evenly matched.

There is also an interesting nuance to the plot, in that the overall plot is funnel shaped (if you look closely), indicating that the relationship flips back to what we saw in part 1 at some point between a 0.5 vs 1 game and a 1 v 2 game.

So when your opponent is creating twice as much xG as you, we can see that by distributing this over >8 shots, you can increase your PPG output by up to approximately 0.1 points compared to distributing xG over 3 shots when involved in open, higher xG total, games.

When the game is “closed”, i.e. xG for both teams is lower, how the weaker team’s xG is distributed has no significant effect on points outcome.

Lets see what happens when we vary the gulf in shooting chance creation prowess between the two teams. We’ll keep all environment parameters the same as before, but this time the strength ratio will be first increased to 3, and then decreased to 1.5.

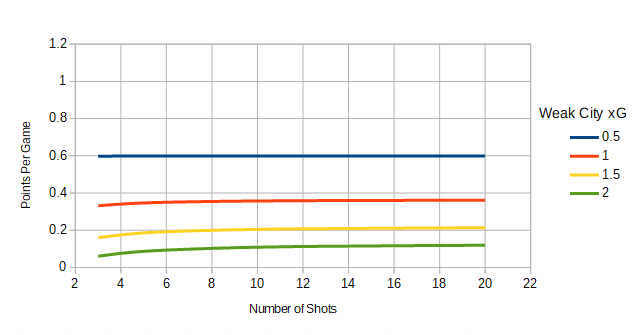

Expected Points per Game vs Number of shots xG is distributed over - Opponent SR=3

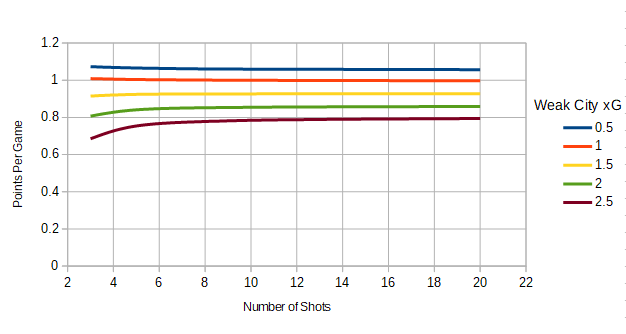

Expected Points per Game vs Number of shots xG is distributed over - Opponent SR=1.5

As expected when the SR was increased to 3 our overall funnel has shifted down the y-axis. The gain seen by closing the game down is strongly pronounced as demonstrated by the distance between the low and high xG lines. This time PPG with an open 1.5 vs 4.5 xG result is around 0.4 pts worse off than a 0.33 vs 1 game, which is comparable to the 0.4-0.5 pts gain we saw when SR = 2.

The PPG increase from distributing xG over a lower number of shots is minimal in terms of absolute PPG gain.

It is also interesting to note that in a 0.5 vs 1.5 game, the weaker team has approximately the same PPG output (0.6 points) as a 1.5 v 3 game even though in the latter case the opposing teams are more closely matched in terms of strength ratio. This highlights the fact that it is actually xG difference as opposed to xG ratio, as well as the distribution effects that are driving the expected points outcome.

So keeping the xG difference as low as possible when you know you are likely to be significantly out-gunned in chance creation is absolutely critical, and how the xG you manage to create is distributed will be of little concern.

Moving to the case where SR was decreased to 1.5, we see the funnel shape is higher up the y-axis and narrower, showing the increased expected points and smaller gap in points between open and closed games we would expect when the teams are more closely matched. We also again see the effect of increased PPG when increasing the number of shots that xG is distributed over, but this time the effect is only significant in 2 v 3 (green) and 2.5 v 3.75 (maroon) games. We still see up to 0.1 PPG difference here between 3 and 12 shots.

Let’s take stock of what we have seen.

-

We’ve reinforced with hard numbers the wisdom of keeping chance quality (measured by xG for example) difference as low as possible when you are the significantly weaker team.

-

When substantially weaker, you can maximise your expected PPG by distributing your xG over a larger number of shots - in practical terms this would mean opting to shoot when lower quality chances are presented rather than keeping possession in shooting areas with the aim of creating a higher quality chances.

-

The PPG difference can be as high as 0.1 across a set of realistic scenarios. If you are the weakest team in your league you are looking at several points difference over a season between distribution types.

-

The effect seen is metric invariant. So you can substitute xG for any metric that you are using to represent goal expectation from chances. You could substitute xG for an “attack danger” metric for example distributed over number of attacks.

There is of course a glaring big fat elephant in the room.

All analysis to this point has assumed that a team’s shooting chance quality distribution is fully controllable, when of course in reality this is not the case. We need to be clear that what has been demonstrated up to now is that if a team had distributed the total shooting chance quality they created in a match into a low number of shots, in many situations they would have a better PPG outcome compared to if this chance quality had been distributed over a larger number of shots. This is different to saying if you know you are a weaker team than your opponent you should always shoot from range rather than try to develop higher quality chances – which this analysis has definitely not shown.

The key conclusion that weaker teams can in some situations maximise their points return from a game by spreading chance quality over a larger number of shots is entirely dependent on the relationship between chance quality and chance frequency being inversely proportional. This means a chance with 0.1 xG can be created twice as frequently as a 0.2 xG shot, and can be created 4 times as frequently as a 0.4 xG shot etc.

It is therefore essential to evaluate how close the opposition adhere to this relationship when defending, in addition to how your own team creates shooting chances. Traits that may skew this relationship might be an opponent that often drops off leaving a crowded penalty area, meaning it is usually more than twice as difficult to increase shooting chance quality by a factor of 2 when in possession just outside the box. Or conversely a team might look to close down with intensity outside of the penalty area to stop shots from range, meaning shooting from range is harder but gaps are left for quick thinking passes into high quality shooting areas. In this situation it may be less than twice as difficult to double shooting chance quality when in possession just outside the box.

As an aside, any deviations from this equilibrium mean the opponent’s defending strategy is exploitable, and as such it always pays to evaluate this value-difficulty chance creation relationship on an opponent-by-opponent basis.

So lets now take what we have found and define some criteria in which our key finding can be safely applied to pre-game strategy rather than just post-game hypotheticals:

| You are the weaker side, but you believe you will be competitive in the game | As shown by more pronounced effect when teams are more evenly matched |

| You are intending to play an open style of football with the aim of creating opportunities. An xG total > 1-1.5 is realistic but so is giving up 2-3 xG to your opponent | As shown by more pronounced effect when games have higher xG totals |

| You believe you have the ability to create 2-4 high quality chances in open play or take shots earlier in the possession far more frequently | As shown by the most significant effects being seen comparing xG distributed over ~3 shots to > 8-10 shots |

Some other points to note:

-

The effect plateaus when xG is distributed over a large number of shots, so there is no further gain from taking e.g. 30 x 40 yard shots.

-

The effect works other way round, if you know you are stronger, increased PPG is seen by concentrating xG into fewer shots in a number of scenarios.

-

You can try out any xG distribution vs another using Danny Page’s excellent calculator. With this you can explore varying individual shot xG values (as opposed to constant used here), vary the number of shots the opponent takes, and verify the opposite effect seen when the opponent is weaker.

Successfully taking advantage of this distribution effect as the weaker or indeed stronger team certainly falls under a “marginal gain” if you subscribe to that philosophy, with points differentials of 0.1 to 0.2 per game seen at the edge cases.

Another way of looking at it is if you do choose to adopt a shoot on sight policy as a weaker side you can take comfort in the fact you aren’t making a mistake mathematically at least.

While there must be caution taken when considering real-world effects, especially our own and opposition team characteristics, tactics, and in-match effects, what we can say is waiting for that “one big chance” while passing up lower quality opportunities may very well be sub-optimal in a number of plausible match scenarios.