-

Distributing a given xG total into few, high quality shots will not maximise points return for some teams in certain match situations – in fact the opposite is true

-

Teams with a known and realised strength disadvantage will achieve increased points per game if their match xG total is distributed across a high number of lower quality shots compared to a low number of higher quality shots

If seminal works exist in the world of football analytics then the following two posts fit the bill:

Danny Page - Expected Goals Don’t Just Add Up, They Multiply

Mark Taylor - Twelve Shots Good, Two Shots Better

In particular, Mark Taylor showed that if there are two teams creating identical xG, the team that has that xG distributed across fewer, high quality shots will outperform the team which has that same xG distributed across more, lower quality shots. It raised the important consideration of distribution of xG rather than just total xG on match outcome.

This conclusion was however based on a scenario of these two teams playing against each other. I was interested in proving this with a simple mathematical methodology as opposed to brute force, and also finding out if this conclusion held across all scenarios. This led to a result I wasn’t expecting, and so I ended up going much further down the rabbit hole than I had planned.

Let’s first create a simple test environment in Excel.

For this environment we will say when a shot is taken we have a simple Bernoulli trial, where probability of success is equal to the xG of the shot. If we have a set of shots taken in a match which have the same xG then we can simply use the Binomial distribution to work out the probability distribution for the number of goals scored from those shots.

Clearly in the real world the characteristics of each shot will vary and so it is highly unlikely a substantial set of shots will have the same xG value. But this simplification will for now allow us to validly demonstrate the principle.*

We use the output of the binomial distribution to answer “if Team A has 10 shots, each shot with an xG of 0.1, what is the probability they will score 0 goals, 1 goal, 2 goals, 3 goals and so on?”

What we want to do is extend this to ask “what is the probability that Pot Shot FC will score more (Win), the same (Draw), and less (Lose) than AFC Walkitin where Pot Shot FC has lots of shots each with low xG and AFC Walkitin has few shots each with high xG but..the total xG for each team is the same?

This will provide a sanity check using an exact binomial distribution method of the outcome Mark Taylor wrote about all those years ago, compared to his brute force approach.

Technical Aside:

For anyone interested in the maths there is way we can generate the goal distribution from real-world varying xG with an exact closed form solution - the Poisson Binomial Distribution.However, it is notoriously difficult to calculate (and your computer will probably use less processing power to generate the distribution using brute force!). There are some approximations out there in Python and R libraries if you are that way inclined.

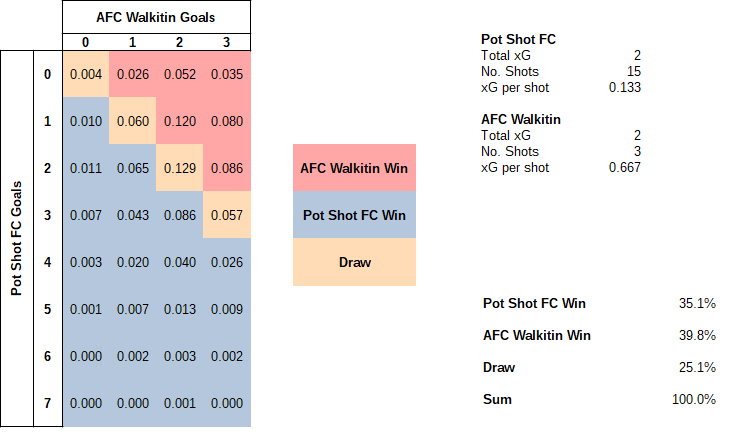

Lets now define the xG distributions of our two Teams.

Pot Shot FC will have a total xG of 2, with this total distributed over 15 shots. Therefore their xG per shot = 0.133.

AFC Walk It In will also have a total xG of 2, with this total distributed over 3 shots. Therefore their xG per shot = 0.667.

We’ll use the BINOMDIST function in Excel to find the probability that Pot Shot FC will score 0,1,2,3…n goals. Once we get to 8 the probability is zero to 3 decimal places so we’ll stop at 7. We’ll then do the same for AFC Walkitin.

So we have a set of probabilities for each of our teams that they will score n goals in the match. We also now have a finite list of scores that could occur in the match ranging from 0-0 to 7-3.

Given we are assuming each team’s goal count is independent we can derive a probability for each scoreline by multiplying probabilities of each team’s goal count. So for example P(0-0) = 0.117 x 0.037, P(1-0) = 0.27 x 0.037 right the way to P(7-3) = 0.002 x 0.296.

Creating a matrix as shown below and summing the outcomes where Pot Shot FC wins, draws, and loses we can define probabilities for the Win, Draw, and Lose outcomes.

And there we have it - Even though both teams have the same xG total, Pot Shot FC only win 35.1% of the time compared to AFC Walkitin who win 39.8% of the time.

Technical Aside:

It should probably be noted for this model we are assuming that a team’s ability to score is independent of their opponents ability to score, and as such each team’s set of probabilities are mutually exclusive.This is not correct in the real world, as clearly the opponent’s performance will be a factor in determining a team’s goal output. However, in our match scenario we know for a fact these shots will occur.

We are now just piecing together what the score could be given those shots occurring. We are also assuming that each shot is totally independent and not dependent on the outcome of another e.g. a rebound.

It is interesting that although AFC Walkitin have no chance of scoring more than 3 goals (and as such Pot Shot FC can win 12.9% of time regardless of how many goals AFC Walkitin score), their domination in lower scoring games is enough to overpower this effect and give them an overall advantage.

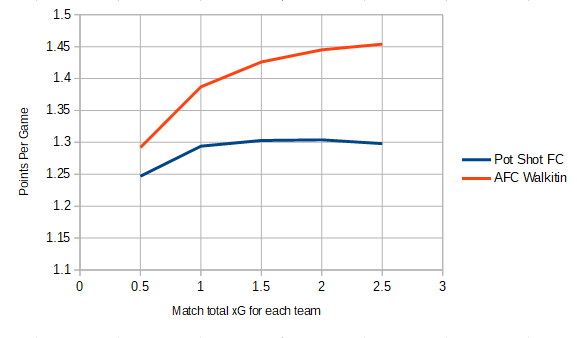

We can also see what happens when the xG total for each team varies. In our example we set our xG total to 2 for each team. Varying this between 0.5 and 2.5, keeping the number of shots at 15 (Pot Shot FC) and 3 (AFC Walkitin) and plotting the expected points per game (3 for a win, 1 for a draw) yields the following result.

Expected points per game vs match xG total for each team

We see that Pot Shot FC’s PPG pretty much saturates at 1.3 pts (and even decreases slightly) from total xG = 1 onward, while AFC Walkitin’s increases, leading to an increased PPG advantage for AFC Walkitin as the xG total increases representing a more open game. We should also note that AFC Walkitin’s PPG advantage is by no means insignificant!

So we have now come to the same conclusion as Mark Taylor by defining the exact probability for each scoreline. And with this tabulated view in Excel we have a simple and easy to use framework to move on to part 2 and back up those headline findings at the top of the page, and importantly, discuss the implications for real word applications.